The Mouse, The Bird, and The Sausage

I am the dungeon master for this adventure. Your roll of the dice will decide if you are to be the mouse, the bird, or the sausage.

Ahh, two, so that makes you the bird. Very well.

Ahh, two, so that makes you the bird.

This story takes place 12,000 years ago. You are in a deep, dark wood, perched at the edge of an oddly shaped clearing. Once, just a wingspan’s breadth from you, one of your brethren, heading home to her nest, fumbled and dropped two acorns, and they both took root in the rain-softened soil. There they grew, standing side-by-side for hundreds of years until one autumnal equinox, a single bolt of lightning flashed through the sky and felled them both. They hit the ground away from each other, lying in neither parallel nor perpendicular lines, but somewhere in between, and stayed in their understory afterlife for 250 years. In time, their dusty burls and skeleton knots will be packed down by many passing paws and feet to become two paths, to become a trading post, a junction, a shop, a village, a city-state, a capitol whose name you would recognize, but not now, not yet. In your time, you are a bird looking down at two rotting trunks in a clearing. You have already cracked your way out of your shell and assumed the feather shapes of your mothers and fathers; you have hopped from branch to branch to catch an updraft, to ride a current and flap your wings in first flight. Just like all the others of your kind who came before you and those that grow alongside you now.

Except.

You were born, I’m very sorry to say, missing a piece. I’m sure if this story took place in our time, we would use high definition scanners, nuclear dye stress tests, electron microscopes, X-rays, CRISPRs even, and identify the exact shape of the piece that is missing. We would take a sliver of beak, run it through our modern medical rapids and manufacture a stem cell to plant in between your pancreas and bile duct and make you make the right shape to fill that hole.

Except.

You live 12,000 years in the past and there is no such technology, especially not in a forest by the remains of two dead trees. And so you are a bird with a missing piece. It is not a clipped wing, or a dropped toe—something like that would be seen and commented on by the other birds. Animals are not like us, they won’t accommodate an aberration, they won’t gently nod and make room. Animals will eat you if they catch a scent of weakness, will shove you with their whole bodies and take the food that you were going to put in your open mouth. They will not slow down and repeat themselves if you didn’t catch which direction they were all about to fly off in. They will leave you behind in a deep well, the sides rising up around you, with just a tiny circle of light high, high overhead that you will never be able to beat your wings hard enough to reach.

No. What is missing is inside you and no one can see it, so you will carry the empty with you through this story.

Roll, please. Wait! One more thing before you roll.

You have something missing, and that makes you different, but so does the extra thing that you have that they don’t. Even in our modern time we don’t have a name for this. It’s best described, since you are a bird, as a piece of grit, a small something that maybe blew up under a wing during your first flight, and lodged itself between two feathers. Whatever it is, it doesn’t fall away, but sits and rubs a tender bit of skin every time you move. You don’t even know it’s there. I only mention it because of how you act among your own kind.

The other birds live typical bird lives, pecking at the dirt for bits of food, working an insect out of a piece of wood, feeling the ground with their little feet after a hard rain to sense the movements of worms underneath. Gathering straw and seed shells and twigs to wind into nests for their coming families. Migrating when it’s time to leave, returning when it’s time to come home.

Sure, you intended to do all these things, too. But for that bit of grit, rubbing and irritating your side. You never think of it, of course, but think instead, now that’s a waste of time. Why would I fly about all day looking for bits of fluff and pieces of string to craft a nest? Why don’t I just live in a cottage? And why would I do all that preening and parading, picking at the sides of my nest to keep everything in line, swooping over puddles to slake my thirst when I could just befriend a mouse, and the mouse could do all the hard work of keeping house and fetching water? And why—at this point, the skin rubbed raw by that piece of grit is very nearly infected—would I dull my beak on tree trunks, or muddy my tongue by pulling worms when Mouse and I could convince a sausage to make our meals?

This is how you, by rolling your 2, came to be a bird who lives with Mouse and Sausage in the cottage in a deep forest.

Now roll again.

Now roll again.

Ahh, seven. A seven gives your claws extra strength and you can lift thick branches and bring them back to the cottage for the fire. The exercise gives you life and you spend the season winging through warm breezes and basking in the sunlight. Things go well. Since you no longer have to flap and peck all day long to meet your basic needs, your skin even began to scab over and looks like it might heal all the way. Mouse labors under the weight of the bucket, hauling in fresh water every morning and Sausage ties on an apron and rolls about in the pots and pans to cook the meals. You coast out after a nice lie in and clamp on a stick or two, nothing too heavy, and bring them back to the cottage for Mouse to tend the fire and Sausage to bake the biscuits.

It’s a resting point, a stability in your life. Needs met, old wounds healing, surrounded by the comfort of one day like the next.

The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage.

Roll again.

Tsk, tsk. Eight. Now things take a turn. A turn of the dial. Faces are dials, are clocks telling time, and time is change, and change is life. Sometimes the change is a changing back. It happens the very next morning when you flit out of the cottage to gather up a stick. You alight on a tree at the edge of that strange clearing, and it is full of your own kind, fattening themselves up for migration.

Full of your own kind.

“Oh, look who’s here,” one of them calls out to the others. “It’s the posh pigeon from the pagoda.”

And it’s there in that word “Pagoda.” That piece of grit, hidden between the “g” and the “o”, and it peeks out and rubs at you. You know you live in a simple cottage, nothing grand, certainly not a pagoda. If they all weren’t so stupid they could all be living in cottages, too.

“You’re a pigeon, not a crow, so don’t try bragging about it,” another clucks up at you. “I’m surprised you even show your face—did the rodent give you a 5-minute break from your labors to come and see what you’re missing? Too late. You’d never be able to keep up with us with that scrawny belly of yours. We’re just about out of here—go back and be a slave for the cold winter, we’ll see you in the spring.”

“Yeah,” another huffed, “see ya in the spring. If you make it that far.”

And with a tremendous roll of the timpani, a boom of kettledrum, smash and crash of the gong, a beat beat beating of wings, they rise as one and blot out the sky.

You are alone with their words, your piece of grit. It rubs you raw all over again. Are you a slave? Are you doing all the work? What actually is harder than gathering firewood? Mouse goes to the well—which is right next to the cottage, by the way, just once a day. And Sausage doesn’t even go that far. No, you are the one who goes way out into the woods, sometimes twice in one day. They’re right.

Roll, please.

Twelve. Ok. You raise a flap. You demand that everyone switch roles. Mouse and Sausage protest, but they can see that you aren’t budging, and eventually, they have to give in. From now on, all you’ll have to do is fetch some water. Mouse is going to cook, and that fat Sausage can go to the forest for wood. Things are better already, just from having decided on change. Your skin even feels better and you drop right off for a lovely, long and restorative sleep.

Roll again.

Three. Early the next morning, you wake to the sound of the front door shutting. Sausage has gone into the woods. You join Mouse at the kitchen table.

“Good morning,” you say. “When’s breakfast?”

“Oh,” Mouse answers, a little surprised. “We can’t have breakfast until Sausage brings some wood for the fire. Once we stoke up the flames, I can boil some water,” Mouse pushes the empty bucket over toward you with a raised eyebrow, “and you’ll have a nice cup of hot tea to sip while I do the cooking.”

You think of all the times you slept in before getting the wood. This is a new day, a new leaf, so to speak, and you decide to do things differently. “Be right back, then,” you say, holding the bucket handle in your beak and flying out to the well.

Roll. Six.

It’s a bit of a chore to get the handle lined up to the hook hanging from the rope. Then you have to turn the spindle and lower the bucket below the surface so that it will fill with water, then raise it back up and try not to spill any. It doesn’t look easy and it isn’t. By the time you get the water back to the cottage, you feel you have earned your tea.

But Sausage is not back with the wood.

You and Mouse sit in silence at the table, waiting for the scuffing sound of a log being dragged up to the front door. There is no sound.

The sun is high overhead when your worry sends you into the forest. You will find Sausage, who must have lost his way, and put this new arrangement back on its track. You fly above the usual paths that the four-legged use, looking to either side in case Sausage fell over. The paths are empty.

Roll, please.

Four. You spot a four-legged, a dog, and so you swoop down to ask if he has seen your friend.

“Sausage? Out here? By itself? Nah,” the dog says, licking his lips steadily between every word. You can’t help but notice the abandoned pile of sticks next to him.

You will have to confront this dog. Roll to see what kind of match this will be.

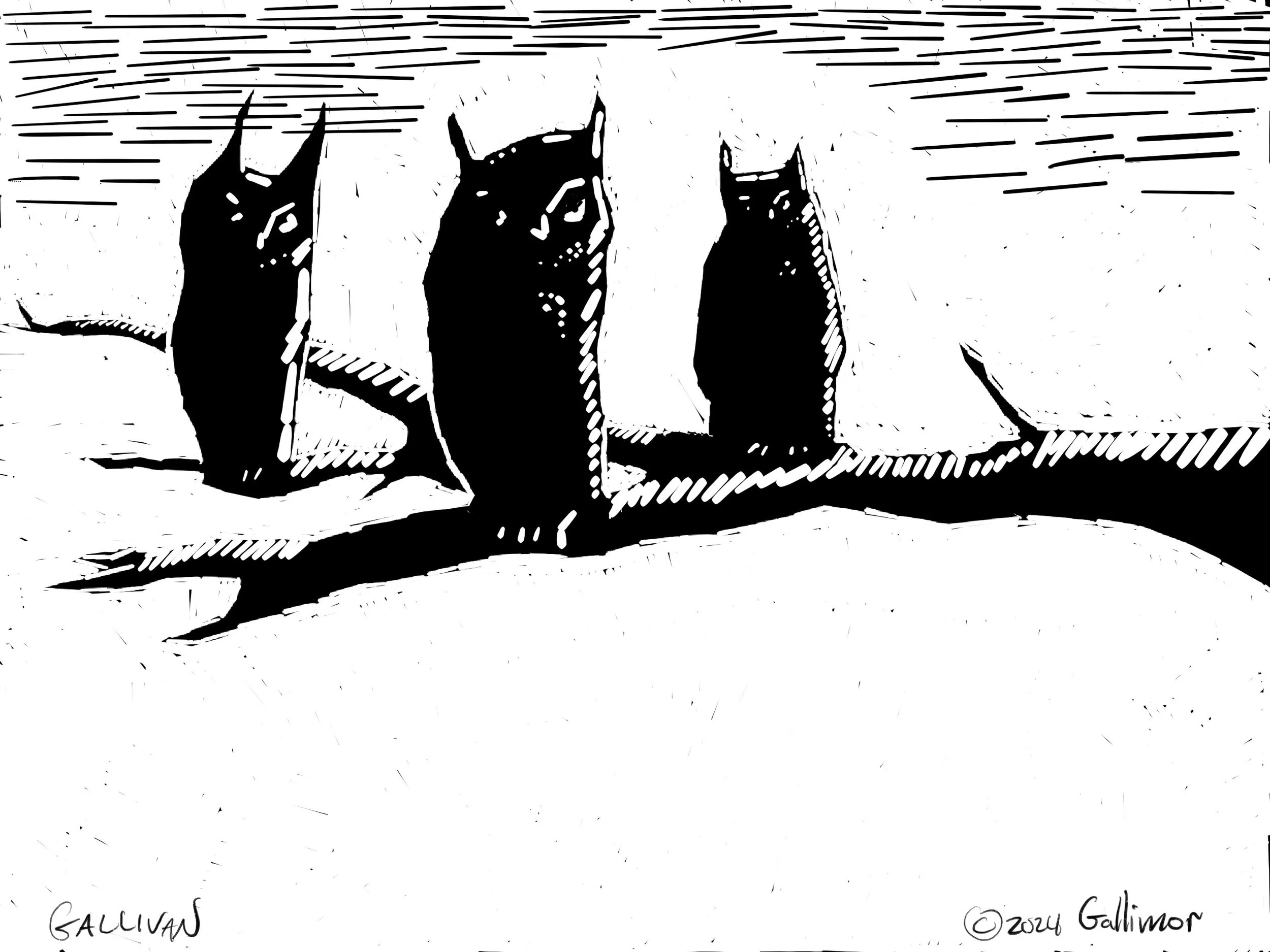

Nine. Nine is a parliament of owls, who line the branches above the two of you.

“State your case,” the biggest owl hoots.

A parliament of owls.

“Sausage, my friend,” you say, “is missing. I think this dog knows more than he’s saying.”

“Say all of it,” the biggest owl hoots to the dog.

“I’m a truthful and pious dog who does not speak ill of my neighbors. But, since you want all of it, then yes, I did see this Sausage. Sausage was carrying forged letters that besmirched all the owls in the forest. Sausage was going to deliver these lies to Fox, who would spread the lies without bothering to find out if they were true or not. I am a truthful and pious dog. I could not let this happen in my watch, so I ate Sausage, a fitting punishment. I ask no reward for selflessly protecting the honor of the owls.”

Roll. You roll a one.

You know that the parliament has been stacked with friends of the dog and that there is no use in protesting further. You return to the cottage with a single stick.

“We are on our own,” you tell Mouse, “we will have to make the best of it. I will gather more wood.” You fly out to the forest again.

Mouse takes the stick and starts the fire. She wants to make a stew for the two of you, but doesn’t really know how. She knows that Sausage did some rolling in the pot to season things, but it’s very hot, so Mouse dips a paw in and pulls it right back out. Steeling herself, Mouse tries again, but falls all the way in and is boiled alive.

You return to a terrible stench—scorched fur and boiled toe. Gagging, you look everywhere for Mouse, under beds, in closets, but can’t find her. In frustration, you toss sticks and bark around, fly up and drop down, stamping your bird feet on the floor. A twig lands next to the pot and ignites. Soon the curtains catch and the wooden spoon and the bed covers until the whole place is ablaze.

Roll now.

A five. You grab the bucket to fetch water from the well, and as you fly out the front door, an ember lodges in your tail feather. It smolders through to your skin just as you reach for the hook, causing you to open your mouth and screech. The bucket falls and hits the stones at the lip of the well and clacks to the ground. You reach for the handle, but the burnt feather causes you to lose your balance and it’s you who drops into the well.

I am also a catfish who lives in this well.

Roll, please.

Two again, like the beginning. You are a bird. I am the dungeon master. I am also a catfish who lives in this well. I am blind, true, but my world is brought to me through sound and what I feel through my whiskers. Now I hear a splash, a frantic paddling toward the moss-slicked stones of the steep well wall. I feel the movement of water through my whiskers until I can reach out and close my mouth over a uselessly kicking foot.